|

Chapter 8

Poor Britannia!

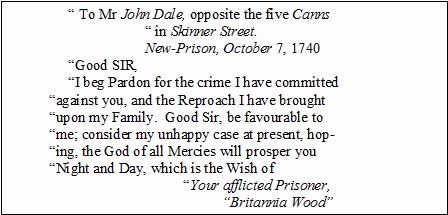

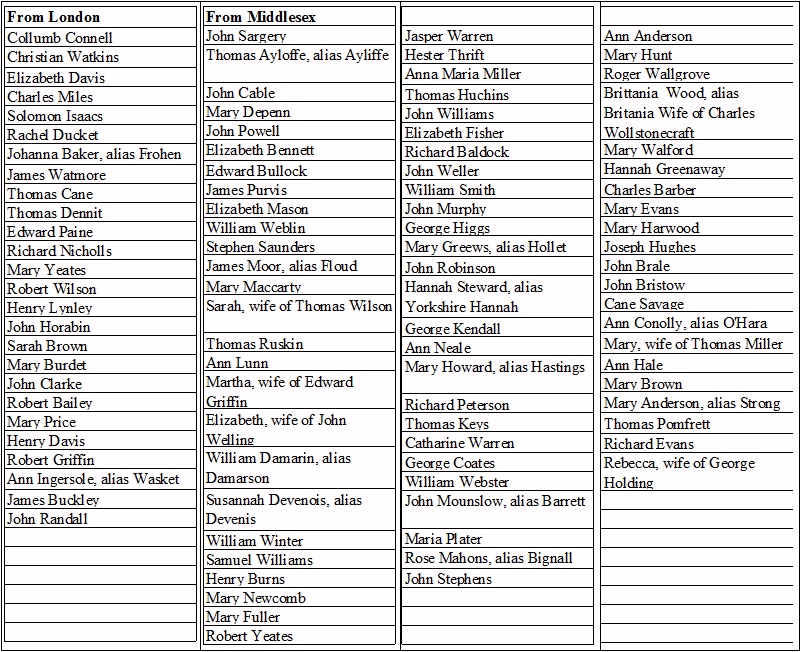

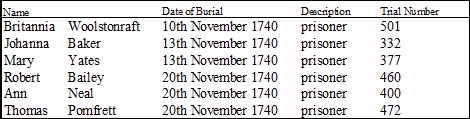

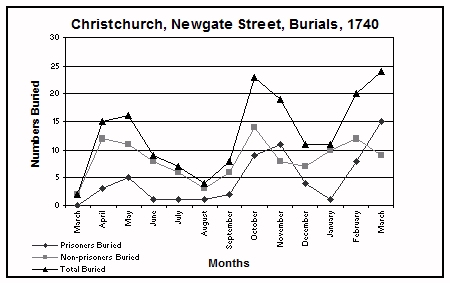

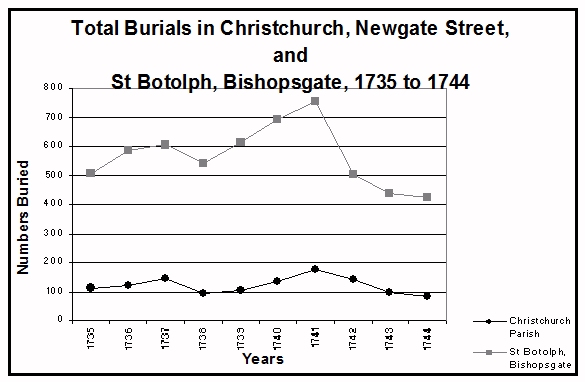

The great advantage of researching a family with an unusual name is to be able to find information relating to the family comparatively easily. Whenever I had a spare moment I had developed the habit of looking up the name, Wollstonecraft, in various different indices at random. The Harleian Society have produced excellent transcripts of registers and I was at the London Metropolitan Archives glancing through their copy of the registers for Christchurch, Newgate Street, when I saw something that really shocked me. As already explained, in 1732 when only seventeen years old, Charles Wollstonecraft had married Britannia Wood. The marriage was "irregular" and may have been "clandestine" too, it was a "Fleet Marriage". Four years later, on 29th March 1736, Edward Bland Wollstonecraft was baptised, son of Charles and Britannia, at St Botolph, Bishopsgate. The entry that surprised me in the Harleian transcript is as follows: "Burials - 1740, Nov. 10 - Britannia Woolstonraft, prisoner" Surely this did not refer to my Britannia! The spelling of her surname was not quite the same but, having such an unusual name, it was unlikely to refer to anyone else. Why was she a prisoner? What had she done wrong? I was determined to find out more. Off, I hurried, to the Guidhall Library to consult the copy of the actual register. Sadly, many registers were destroyed in 1940, through the enemy action of World War II, and the register I wanted was one of those. I felt very grateful to Mr Willoughby A Littledale who had made the transcript for the Harleian Society back in 1895; without that, record of her burial would have been lost. I wanted to know why she had been imprisoned and in that I was very fortunate. The Guildhall Library holds, on microfilm, copies of published reports of Old Bailey Trials, dating from 1684 to 1913. The original papers had been printed and sold by T Cooper of the Globe, Paternoster Row, at sixpence a copy. In their time, the papers were very popular and sold well. People of London were eager to know about crime and punishment in the city. The wagon taking the condemned to execution at Tyburn (now the site of Marble Arch) was a popular event. Crowds would line the way to vent their feelings on the wretched prisoners. Shouts of scorn might echo out; an onslaught of rotten tomatoes might greet them at every turn. On the other hand, if the villain were a popular figure, an infamous rogue who had captured popular imagination, that final journey might be to a chorus of lusty cheers. The whole grotesque spectacle was a form of entertainment and not to be missed. The microfilm copies are in date order with indices. If she had died in November 1740, I assumed her trial would have taken place shortly beforehand and there, indeed, I found her in an index under her maiden name:" ‘T’ Britannia Wood, Trial Number 501". I was not sure what the ‘T’ stood for, but I was soon to find out. The original published report is fascinating. There could be no doubt that the case referred to Britannia Wollstonecraft. She had used her maiden name, Wood, which was in the record of her marriage to Charles. She was accused of stealing three pieces of silk and cotton, valued at £2 2s (two guineas), from the shop of John Dale of Skinner Street, on Tuesday, 30 September 1740. John Ogilby’s map of London, 1676, does not list Skinner Street in its index. It does show Skinners’ Rents and that led westerly out of Northern Folgate, south of and parallel to Primrose Alley.1 John Rocques later map, of 1747, shows the same roads with new names, Skinner Street and Primrose Street, both leading out of Bishopsgate Street Without into Long Alley.2 Britannia was tried two weeks after the crime was committed. At the trial, John Dale said he had not realised the cloth was missing until Thursday, three days after he had had the cloth brought home from the "Calenders". According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a calender was a steam mangle, a roller used to press material. Calender Court was just off Long Alley. He made a great "noise" about it, a great fuss to bring attention to the crime whereby he might discover whether anyone had information that could help him locate his property and find the culprit. It was not long before he learned where some of his cloth was on sale. Without delay, Britannia was arrested on suspicion and charged with the crime. At first she denied all knowledge of the robbery, but then she tried to bargain with the shopkeeper. If he freed her she would tell him where he could find the rest of his property. She had pawned the cloth in her maiden name, Britannia Wood. Before the justice, she confessed. She said that she had gone into Dale’s shop for some checked material for a gown and, when his back was turned, had made off with the merchandise. John Dale followed Britannia’s directions to find his cloth, but did not drop the charges, saying that he was concerned about other items that had gone missing and might also have been stolen. A week after the crime, writing from Newgate Prison, Britannia begged him for mercy. The letter was read out in court:

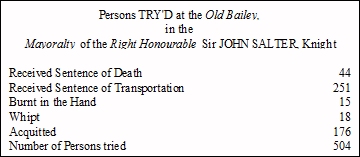

Witnesses were called and Britannia made one last appeal: "I beg the Mercy of the Court; I have no Friends now, they will be here to-morrow". The verdict was guilty and, sadly, it seems this was correct, she had confessed. She had stolen the cloth to pawn it and so, it would seem, she must have needed the money. Why was she so desperate for money that she had turned to stealing? Was it to buy food for her child? Edward Bland would have been just over four years old. No mercy was shown to Britannia, despite her sad note; "Your Afflicted Prisoner", was she ill? If she were not sick before she was thrown in gaol, she would very soon succumb to ill health; conditions were abysmal. I was relieved that she had not received a sentence of death, but her sentence was almost as harsh, she was to be transported for seven years. Such a sentence could well result in her death. If she survived the long voyage, she had no idea what to expect when she reached her destination. Very few transported convicts ever returned to this country. Until 1834, the Middlesex and City of London Sessions of Gaol Delivery were held at the Old Bailey Sessions House, situated alongside Newgate Prison. As was the procedure, Britannia’s trial would have been heard before the lord mayor of London who, at that time, was Sir John Salter. It was his eighth sessions since taking up the position and, so far during his term of office, he had heard 504 cases. The following interesting statistics appear at the end of the report of those sessions, 18th October 1740:

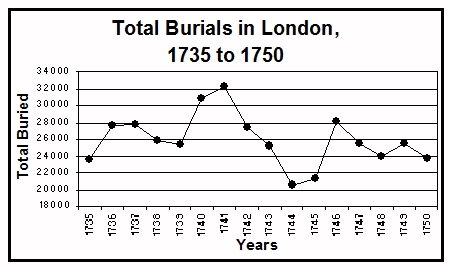

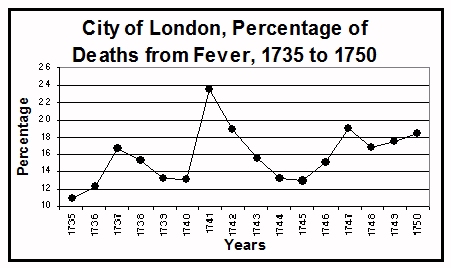

Britain had been sending convicted criminals to America and the West Indies from the early seventeenth century. In the developing colonies, there was a severe shortage of fit, strong labourers to undertake the physical work that was needed to cultivate the land. The authorities believed the toil and industry, the convict would find in the new territories, would reform the offender from his criminal ways and help him settle to a better way of life. It became the custom for those under the sentence of death to be offered a pardon, if they accepted transportation. An act of Parliament, in 1718, set the length of transportation to fourteen years, in the case of capital punishment, and seven years, for those guilty of lesser offences. Transportation of convicts to the New World lasted until 1776, when it became impossible to continue the practice because of the American War of Independence. By then, as many as 40,000 people had been sent. Without this means of reducing the prison population, gaols soon became horrendously overcrowded. Looking for a solution to the problem, a penal colony was set up in Tasmania and the first convicts shipped there in 1803.3 Newgate Prison Newgate Prison dates back to at least the beginning of the thirteenth century. Despite being rebuilt and altered on various occasions, it remained a vile place of horrors. After the Great Fire, it was refurbished on a grand scale and the outside adorned with stone statues, but this imposing exterior contrasted greatly with the grim conditions within. The poorer classes were separated from the more wealthy and confined together in one large, dismal room, with felons further divided from debtors. The condemned were manacled, awaiting execution. In the press-yard, inmates were tortured to extract confessions. Below ground level was a miserable area known as Stone Hold. Here, with no daylight, the hapless prisoners would be left to lie, in the dark, on the bare stone floor, where their moans and pleas for mercy would go unheeded. The gaol was intolerably overcrowded. The con-victs remained there for long months or years, many to die a forlorn and deplorable death in the filth and overwhelming stench. Amongst the hardened criminals and those awaiting trial, were others confined for trivial offences, the poor and starving, who might have stolen simply to keep alive.From time to time, philanthropists had tried to bring comfort to the malefactors. One such, in 1744, was Silas Todd. He regularly visited the gaol soon after Britannia was incarcerated there and, from his book, we learn of the terrible suffering she would have had to endure. The prison was rife with all manner of contagious diseases. The stifling atmosphere, with little ventilation and poor supplies of water, all hastened their spread. The most prevalent was gaol fever, or typhus, an acute, infectious disease. The symptoms include severe headache, high fever, a dusky rash and delirium. Transmitted by lice and fleas, good hygiene is necessary to keep it under control. In such cramped, insanitary conditions, there would be nothing to prevent the disease infecting all the unhappy wretches within.4 Records at the Corporation of London Records Office, reference MSS 54.8, show the concern regarding the need for ventilation at Newgate Gaol with accounts of "several persons seized with gaol distemper, working in Newgate". Ventilators were introduced in 1747 but, three years later, a letter dated 15th October 1750 from John Pringle to Alderman Jansen reveals the continuing gravity of the situation with the disease raging unchecked. During the sessions of May 1750, the lord mayor, Sir Samuel Pennant, two judges, various lawyers and members of the jury died as a result of contracting the disease. The court was packed to capacity; many had come to hear the case of one, Captain Clarke, accused of murdering Captain Turner. One hundred prisoners were to be tried that day and they were crammed together into two small rooms. The pungent odour pervaded the courtroom and was blamed for carrying the infection to the various officials and members of the public. It became the custom to spread sprigs of bitter strong-scented rue on the prisoners’ dock in an attempt to purify the air. More ventilation was introduced in 1753 and there is a note of the costs involved. However, the size of the ventilation machine alarmed those living in the nearby area, who complained bitterly that the noxious fumes would infect the whole neighbourhood. It seemed quite likely that Britannia might have died of this terrible disease and I thought that a post-mortem record could possibly have survived to confirm the cause of her death. Because Newgate Prison was within the city of London, I decided to begin my search in the Corporation of London Records Office, but was unsuccessful in finding anything. The offence had been committed in Middlesex, perhaps I should try the London Metropolitan Archives. Before moving on, on the advice staff I consulted "English Convicts in Colonial America, Volume I, Middlesex 1617 – 1775". This extremely useful book, one of a series compiled and edited by Peter Wilson Coldham, provides not only an index to those transported but also details of their crime. There I found the following entry: "Wood, Brittania als wife of Charles WOOLSTONECRAFT of Christ Church S October 1740 s silk & cotton T Jan 1741 Harpooner to Rappahannock Va". Now, I had a date for the transportation. The river Rappahannock is in Virginia, USA, and flows into Chesapeake Bay. Not far away at Jamestown, English settlers had founded Virginia in 1607. During the course of the previous two hundred years people, mainly Protestants, had been settling along the East Coast of America, escaping religious persecution and looking for a better future for their families. I was puzzled. How could Britannia possibly have been transported? I understood she had died; could the entry in the burial register for Christchurch have referred to an unfortunate child that Britannia might have had with her in prison? Had she given birth whilst in gaol? Not very likely, I thought. The register described the deceased as "prisoner" and a child accompanying its mother would hardly be described in this way; "infant" would have been more appropriate. There might be no surviving record of the death of a prisoner taking place after sentencing at the court sessions and before the order for transportation could be carried out, but surely the lists of those actually put on board the ships would show whether Britannia had been included. Perhaps the Public Record Office in Kew could help. Contractors were engaged by the state to undertake the transportation of the sentenced convicts. The Treasury paid these contractors and the details were recorded in the Treasury Money Books. |