- Marmoy, Charles F A (editor), The Case Book of ‘La Maison de Charité de Spittlefields’, 1739-41, Publications of the Huguenot Society of London, quarto series, 0309-8354. 55

- Waller, William Chapman, Extracts from the Court Books of the Weavers Company of London, 1610-1730, Publications of the Huguenot Society of London, Vol XXXIII

|

Chapter 9

Edward Wollstonecraft, Weaver and Citizen of London

Edward Wollstonecraft described himself in his will as a "Weaver and Citizen of London". The term, ‘Citizen of London’, would suggest that Edward held the freedom of the City of London. Before the middle of the nineteenth century, it was necessary to hold this freedom in order to ply a trade or make a living within the City limits. A freeman of a City livery company could apply for the freedom of the City. It would appear that Edward held the freedom of the Worshipful Company of Weavers. The Worshipful Company of Weavers has a particularly long and interesting history. This has been recorded in various publications by the company, amongst which is a very informative and illustrated book written by Valerie Hope entitled, "The Worshipful Company of Weavers of the City of London". Similarly, for those researching an ancestor who was a member of the company, much help can be gained from "The London Weavers’ Company, 1600 - 1970", by Alfred Plummer, and published in 1972 by Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. The book not only covers in great detail the history of the company, but also records incidents concerning many of its members, giving their personal details. With a documented history going back nearly 900 years, the company is the earliest recorded group of craftsmen or traders in the City. The weaving industry was of particular importance to the country and the company held a position of some power and influence. However, over the centuries, times of prosperity have been interspersed by periods of extreme hardship for members of the Company of Weavers. During the reign of Edward III, weavers started arriving from Flanders, bringing their skills to this country and leading to unrest that lasted over a hundred years. Again, in the sixteenth century, the weavers were to face competition. Religious turmoil on the Continent forced a third of the merchants and manufacturers of the great market of Antwerp to seek refuge on the banks of the Thames. London developed into the general market of Europe. Gold and silver from the New World was sold, along with cotton from India, silks from the East and home-produced wool. Following the St Bartholomew Massacre in France, August 1572, the first wave of French Huguenots arrived, escaping cruel, religious persecution for their Protestant beliefs. Their outstanding expertise, particularly in the weaving of silk, did much to revitalise the industry.1 , 2, 3Imported goods were increasingly reducing the sales of home-produced fabrics. From early in the seventeenth century, the East India Company had started facilitating the importation of Indian textiles, calicoes from Surat, chintzes from the Coromandel, with fine silks and muslins being brought from Bengal. In 1660, when the monarchy was restored after the Civil War and Oliver Cromwell’s strict Puritan rule, the weavers celebrated enthusiastically to show their support, hoping for an improvement in their livelihood. Friendly rivalry seems to have existed between the weavers and the butchers, as an entry in the diary of Samuel Pepys records. The occasion was St James’s Day, a holiday and time for a little amusement: 26th July 1664: "Great discourse of the fray yesterday in Moorefields, how the butchers at first did beat the weavers (between whom there hath been ever an old competition for mastery), but at last the weavers rallied and beat them. At first the butchers knocked down all for weavers that had green or blue aprons, till they were fain to pull them off and put them in their breeches. At last, the butchers were fain to pull off their sleeves, that they might not be known, and were soundly beaten out of the field, and some deeply wounded and bruised, till at last the weavers went out tryumphing calling, £100 for a butcher".4 Any such skirmish was far removed from the events of the following year, the year of the "Dreadful Visitation". The General Bill of Mortality for the year ended 19th December 1665 contains the following revealing analysis:

Figure 28: Analysis of causes of death as shown in General Bill of Mortality, year ended 19th December 1665

London had seen previous epidemics of the plague, particularly in the years 1603 and 1625, but the death tolls had not been to the terrible extent as that of the year 1665. It is thought that concern over the numbers, who had died in the years when the plague was prevalent, initiated the recording of causes of death in the Bills of Mortality. The diagnoses are quite fascinating. They were determined by "searchers". When the sexton of the church in the appropriate parish was told of a death, he would contact the searchers, old women who would view the corpse and report back to the sexton the cause of death.5 With no medical qualifications, the accuracy of the searchers’ opinion is questionable. Nevertheless, the frighteningly high figure of deaths from the plague stands out quite clearly. Transmitted by fleas on rats, the epidemic reached its peak at the end of August and beginning of September, in that particularly hot, sweltering summer. Figures demonstrate the large proportion of total deaths that was attributable to the disease.

The General Bill of Mortality also shows the total numbers of casualties for the year in each parish and gives totals for the areas, as follows: 6

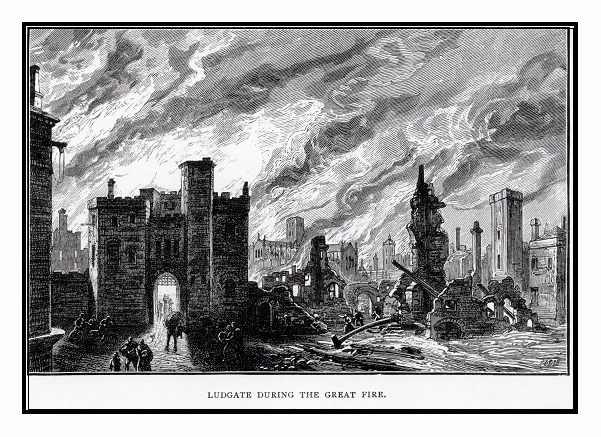

No fewer than 68,596 people in London perished as a result of the Great Plague. The population of London, estimated by Graunt in his dissertation on the Bills of Mortality, would have been around 400,000. The death toll from the plague represented about 17% of the total inhabitants of the 130 parishes in the City and its surrounds.7 At that time, the weavers lived mostly in Southwark, with lesser numbers in Cripplegate and Shoreditch, and a few in Westminster. The plague raged out of control in the shabby tangle of courts and alleyways where the weavers dwelt. The rich moved out of the City, some people escaped infection by living on boats and barges on the river, but the poor remained. Conflagration followed with, as described by Samuel Pepys, "The Great and Terrible Fire of London, September 2nd 1666". Unprecedented destruction on such an overwhelming scale brought catastrophe to the City. It raged for four days before finally being brought under control on Thursday, 6th September. By then, little of the City remained standing. St Paul’s Cathedral was burnt to the ground, together with no fewer than 87 of the 109 churches. Fifty-two of the company halls were destroyed, including Weavers’ Hall. Also reduced to ashes were the foul and polluted labyrinths of slums, rife with the plague the year before. The fire had helped to destroy remaining pockets of infection.

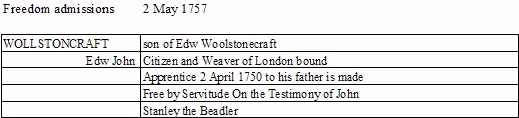

Thomas Vincent, a Protestant preacher of the time, described the people of London as "now of the Fields". With nowhere to lay their heads they, "Lie all night in the open air with no other canopy over them, but that of the heavens". In the area around Islington and Highgate, the diarist John Evelyn reported, "200,000 people of all ranks and degrees dispersed, and lying along by their heaps of what they could save from the fire, deploring their loss". Until 25th September, it was not possible to complete Bills of Mortality and so the death toll from the fire could not be recorded in them. The figure is not considered to be great. However, many would have died in the months following as an indirect result, trying to survive the approaching winter months without shelter or means of earning a living. In view of the crisis and to avoid tragic loss of life, Charles II took urgent action. He issued an order that those in the surrounding towns and villages unaffected by the fire should accommodate the homeless. More overseas immigrants were arriving.i In 1685, Louis XIV of France revoked the Edict of Nantes, taking freedom of worship away from the Huguenots. Over fifteen thousand left France and sought shelter in this country, the vast majority making their home in London. Many were skilled artisans and the silk weavers congregated mainly in the Spitalfields area forming their own community. They lived in specially designed cottages where weaving was conducted in the upper rooms. Here, maximum light could be admitted through wide-framed, latticed windows, to aid the skilled craftsmen in the intricacies of their art. The newcomers were not always welcomed. The population of Spitalfields was greatly increasing but sales were not keeping pace; production was outstripping demand. Imported fabrics, particularly those from India, had become very fashionable. Other factors played a significant part in determining the fortunes of the population in general. There was much poverty generally and rises in the cost of food led to severe hardship. The working class depended on bread for its diet but the price was determined by the abundance of the harvest. In years of a poor harvest, the price would increase to the point where those already eking out a bare existence would be faced with starvation. In addition, when the price was high, huge profits could be made by the farmers, more so if they exported their wheat and grain abroad, increasing the shortage in this country. From time to time, parliament intervened and imposed an embargo on the export of corn. Importing food was no solution, tariffs were levied to pay for the war with France and, between 1690 and 1704, these were quadrupled. Rioting was not uncommon, the poor needed to draw attention to their plight. At the end of the seventeenth century, the harvests were bad. This, coupled with the fall in demand for their products, led the weavers to put pressure on the government to curb the import of textiles. Unrest intensified and East India House was stormed. The government passed legislation that was intended to support the weavers cause; calicoes painted, dyed, printed or stained in India, China or Persia and other fabrics including silks should not be used or worn in this country. This brought some relief to the weaving industry, but there was no penalty imposed on the wearers of these fabrics nor was there a restriction on calicoes printed elsewhere. Foreign textiles did not lose their popularity, calicoes continued to be in vogue and any improvement to the local industry was short-lived. In 1719, the weavers took matters into their own hands and marched through London, spoiling the clothes of those wearing Indian calico. More legislation was introduced prohibiting the wearing of calico and imposing the death penalty on weavers who might use violence to effect their aims. In 1740, the harvest failed once more and the situation was bleak. On this occasion, the effects were particularly grave, many died from cold and starvation. Rioting took place throughout the country; people tried to prevent the continuing exportation of corn. This was the year of Britannia’s trial. Had she been amongst the starving? Between the years 1756 and 1776, there were huge variations in the price of corn. Civil unrest and food riots became commonplace. At this time, the silk weavers of Spitalfields and their families were facing serious hardship and distress. On 14th May 1765, more than three thousand marched to Westminster to call attention to their needs. They returned peacefully, but, the next day, the House of Lords rejected a Bill that would have used tax measures to restrict the importation of Italian silks. Bitterly disappointed, on 15th May they marched again to demonstrate their protest. The situation grew out of control as militant individuals and agitators seized the opportunity to wreak havoc. The Duke of Bedford and Bedford House were attacked; mob violence ruled the streets. Lives were lost as rioters swept through the City, vandalising property, looting and robbing all in their path. Normal day to day life in the City was totally disrupted. The House of Lords had no alternative but to issue directives to restore calm. The Riot Act was read and order finally returned after military intervention.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The pleas of the weavers could not be ignored and, shortly afterwards, the government passed an Act aiming to reduce the imports of silk goods, but this brought little improvement. Unrest and recurrent civil disturbance continued. Low wages and the introduction of mechanisation led to violent action and it became necessary to station guards in Spitalfields. The predicament of the weavers and their families was not relieved until the passing of the "The Spitalfields Act" in 1773, whereby wages and prices were regulated. However, the Act applied only to that particular district and manufacturers simply took their business elsewhere to avoid legislative control. This had the effect of taking work away from the Spitalfields weavers, causing more misery. Additionally, fixing wages meant that there was no reward for exceptional work. Without that incentive, progress became slow, bringing some stagnation to the local industry.13 In 1830, about 100,000 people lived in the Spitalfields area and half of those sought their livelihood from the weaving industry. Many were the descendants of the Huguenot immigrants of 1685. They exported cloth all over the world but conditions continued to be poor, the weavers worked long hours for low wages. Membership of the company had fallen steadily throughout the eighteenth century. In 1701, there were 5,785 members, including officers, assistants, livery, widows and others. By 1800, this number had fallen to 983. One way by which a person could be admitted to a City livery company would be by completing a period of apprenticeship and proving a certain level of skill and competence. I turned my attention to the Register of Freedom Admissions to the Company of Weavers, held at the Guildhall Library. Under reference MS 4656/6 is recorded the freedom of Charles Woostonecraft on 11th October 1736. This shows that Charles, like his father, was a weaver too. He may well have been apprenticed to his father to learn the craft. Charles was baptised on 22nd August 1715, probably when only a few days old, thus indicating that he was just twenty-one years when he completed his seven years apprenticeship and received his freedom. It is, however, interesting to note that Charles had married four years previously, whilst he was still an apprentice. When an apprentice bound himself to a master for a number of years, the terms of the apprenticeship were very strict. The master agreed to teach the apprentice the skills necessary and provide him with food, clothing and shelter. In return, the apprentice pledged his absolute loyalty to his master and agreed not to incur any loss to him by activities such as gambling. If the apprentice wished to buy or sell, he had to seek his master’s permission. Similarly, there were rules regarding visiting taverns or playhouses. The terms also stated quite clearly that the apprentice might not "contract Matrimony" during the period of apprenticeship. Charles was very young when he married. Their son, Edward Bland Wollstonecraft, was baptised on 28th March 1736, shortly before Charles received his freedom. At only 21 years of age, Charles had a wife and child to support. With the fluctuating state of the weaving industry and huge variations in the price of bread, the family may have been struggling to make ends meet during those first four years of Edward Bland’s life. Could this explain why Britannia, desperately trying to feed herself and her child, had turned to stealing for want of money? An indication of the poverty the family may have been suffering in earlier years could be the high number of deaths in infancy of Edward’s children. His first-born appear to have been twins, but they died only three days after their baptism. Three more of the children from his first marriage died before they were six months old and another two before they were five years. On 31st March 1736, three days after Edward Bland’s baptism, Edward John Wollstonecraft, Edward’s son from his second marriage, was born. There was very little difference between his and Edward Bland Wollstonecraft’s ages; Edward John was just one month younger than his half-nephew. For the few years after Britannia’s death, the children could well have been brought up together. Certainly, in the closely-knit community of the Spitalfields weavers, they would have shared many of their childhood experiences. A third child was born to the family in the spring of the year 1736. The entry following that of Edward John in the baptismal register for St Mary’s, Spital Square, is that of Mary, daughter of Isaac and Elizabeth Ann Rutson. She must have died whilst very young as her parents gave the same name to another daughter born seven years later. In April 1749, Charles was living in Dunning Alley, Bishopsgate. He appeared as a witness in a lawsuit, Wilcox v Hills. Giving his occupation as weaver, he described how in June 1747, whilst residing at the sign of the "Ship" in Primrose Street, he had provided dinner for those involved in the court case. He had been acting in the capacity of an innkeeper.14 Both Edward’s surviving sons followed him into the weaving profession and I found a more complete record of Edward John Wollstonecraft’s apprenticeship and subsequent freedom in the Freedom Admissions Register for the Worshipful Company of Weavers, held at the Guildhall Library under their reference MS 4656/7: 15

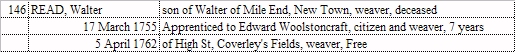

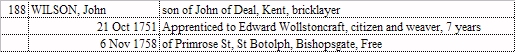

As well as William Cranwell and Joseph Newsom apprenticed to Edward Wollstonecraft, the Company’s Minute Books of Apprenticeships, Turnings Over and Freedoms, held at the Guildhall Library under reference MS 4657A/5, also records the following:

and

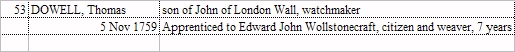

Similarly, in addition to Edward Woodstock Rutson apprenticed to his half-uncle, Edward John Wollstonecraft, in 1760, a year earlier and two years after Edward John receiving the freedom of the company himself, the same Minute Book records the following:

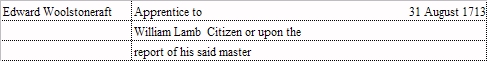

However, in an earlier Register of Company Freedoms covering the years 1708 to 1719, at reference MS 4656/5, I was delighted to find this entry:

It is a short walk to the Corporation of London Records Office to check the Alphabets of the City of London Freedom Admissions. There I found: "August 1713 Woolstoncraft, Edward Weaver ". This led me to the City of London Freedom Admission Papers to discover, waiting for me, the following little gem:

"This Indenture witnesseth that Edward Woolstonecraft son of Arnold Woolstonecraft of the parish of St Andrew’s Holborn, Weaver, doth put himself Apprentice to William Lamb Citizen and Weaver of London and with him (after the manner of an Apprentice) to serve from the day of the Date hereof unto the full end and term of seven years, from thence next following to be fully complete and ended."

The indenture is dated March 1702/3, "in the second year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lady Anne, Queen of England", when Edward would have been fourteen years old. Edward’s father’s name is just legible, Arnold Woolstonecraft. The document would have been produced as evidence to confirm the details of Edward’s apprenticeship so that he could subsequently gain his freedom of the City. Apprenticeship lasted not less than seven years; a few might have lasted longer but that would have been exceptional. The apprenticeship would be followed by a period of two or three years working as a journeyman, before application could be made to become a freeman of the Company. The weaver would then have been about twenty-four years old. I was delighted with the find, but tapping the family name into the search engine for the Public Record Office was to lead me to uncover an even more interesting and curious, possible family connection.

i Two of the Huguenot Society Publications are of particular relevance when researching the weavers of London:

|